World Art Day 2022: Some thoughts on NFTs

In 2019, UNESCO named April 15 World Art Day. It provides an opportunity to reflect on the state of art throughout the world in terms of new developments, cultural shifts and the health of the markets. In a typical year, the conversation might be about the passing of important artists, some grand new venues, blockbuster exhibitions and new auction house records. But this has not been a typical year for several reasons, not the least of which is COVID-19.

With the pandemic, we saw the birth of Zoom culture. Across many platforms, we now communicate differently with family, friends and colleagues.

It was also just a year ago when Christie’s auction house sold its first purely non-fungible token – commonly called an “NFT.” NFTs allow artists to register their work on a blockchain thereby creating a unique digital asset.The work was Beeple’s NFT associated with Everydays: the First 5000 Days, a digital collage of images from the artist’s "Everydays" series. While it was a first for Christie’s, the news item is (still) that the NFT sold for $69.3 million. The sale was an outlier – the next closest NFT sold for a fraction of Beeple’s blockbuster – and it put the artist in rare company as one of the most expensive art sales in history.

This big Beeple sale undoubtedly inspired a year of incredible growth for NFTs. Over the past couple of years, OpenSea – the largest NFT marketplace – saw sales soar from $8 million to $5 billion before dropping back down to $2.5 billion. Such a drop raises questions and concerns. As well, OpenSea recently admitted that through its free NFT minting tool, 80% of the new NFTs were plagiarized or spam. So, this is hardly a settled marketplace.

The key idea behind NFTs is that they are immutably unique and forever traceable. One element of their appeal is that they offer artistic control: Through an NFT, a creator can clarify ownership, copyright, reproduction rights or even claim a cut in all future sales.

So, are NFTs art?

The easy answer is: no – they are a market tool, like art gallery representation or a contract. The honest answer is: rarely. By creating a unique and transferable record on the blockchain, NFT makers can make trackable objects in limited quantities that can be sold. In fairness, much of the race of the NFT market had nothing to do with art; instead, it was about speculation and collectibles. Sports NFTs are huge, and that shouldn’t be surprising since the obvious model for explaining NFTs is baseball trading cards. As well, most of the “art” NFTs are of dubious quality. Some of the most famous feature cartoon images of lazy, entitled animals made unique through AI-driven variations. The amounts for which some of these sold created a race that ultimately has come to feel like a pyramid scheme. We read articles about those rare success stories, and we hear far less about the fact that the vast majority of NFT makers lose money. And, of course, there is the controversy about how much energy it takes to create and update NFTs. A famous French climate activist, Joanie Lemercier, for example, put up six NFTs for sale on Nifty Gateway. They sold in 10 seconds for many thousands of dollars. A success, right? To her horror, Lemercier then learned that the sale used 8.7 megawatt hours of energy – enough to run her entire studio for two years.

While NFTs offer an entirely new way to think about the art market and the professional details of rights and ownership, the system is still in an exploratory phase. When you own an NFT, for example, you technically own something, but there can still be infinite digital copies of that image out there in the world. And blockchain minting costs money and uses large quantities of energy. But it’s too soon to write off NFTs despite the still-expanding reality of theft, fraud and plagiarism. Consider the quickly expanding cultural economy in Saudi Arabia, for example: It’s a country with a minimal commercial art gallery infrastructure, but Saudi society is one of the most digitally sophisticated and largest consumers per capita of online culture. Saudi artists should be watching closely what happens with NFTs.

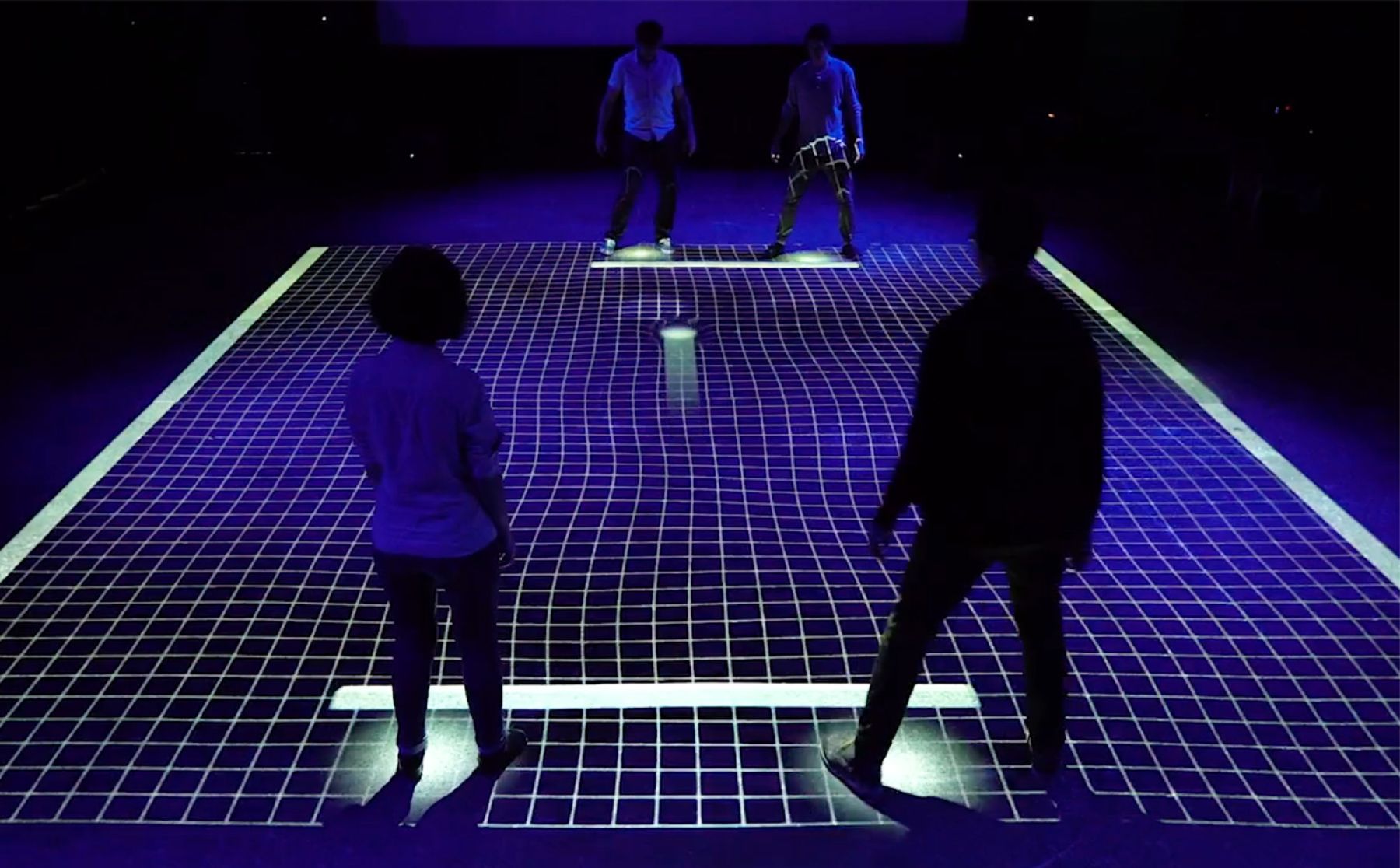

What will 2022 look like for art? The pandemic has led to the permanent closing of up to 15% of the world’s museums. People are being more guarded about jetting off to every major art fair. Movies are giving ground to the Netflix series model. The big art auction houses seem to be growing in stature and China has actually overtaken the United States in that market. Online platforms such as Saatchiart.com, Artfinder.com, UGallery.com, and others are becoming more user-friendly for both artists and collectors. We are also watching the meteoric rise of immersive arts (VR, XR, etc.) – and their possibilities when combined with NFTs could well lead to new and deeply compelling forms of art.

To be sure, this is an unsettled and unsettling time, but rarely – if ever – has there been a time of so much possibility in the arts.

- By Daniel Kany